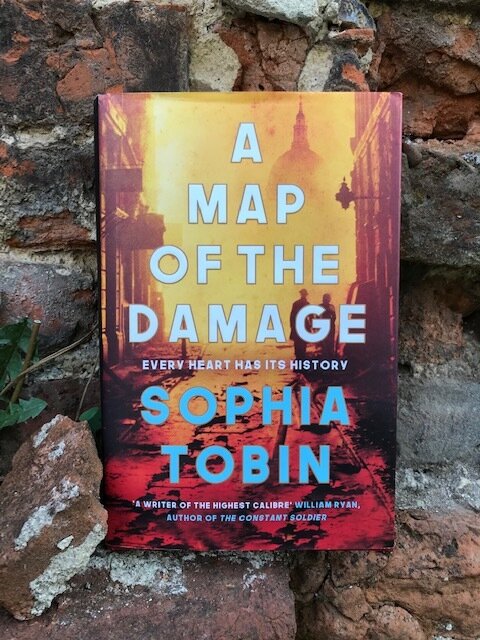

I am delighted to introduce and interview best-selling author Sophia Tobin about her smashing fourth novel A Map of the Damage.

Sophia’s first novel, The Silversmith’s Wife, was a Sunday Times bestseller, and shortlisted for the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize.

Her second novel, The Widow’s Confession, was published in 2015, and her third, The Vanishing, in 2017, both of which have won accolades from a host of media outlets, including the Sunday Times, the Daily Mail, Country Life, and the BBC History Magazine.

Thanks very much to Sophia for her time and insights into the writing of the fascinating and highly enjoyable A Map of the Damage.

For a real treat, you can read a synopsis and first chapter of A Map of the Damage on Sophia’s website here

Sophia Tobin

INTERVIEW

Kate: A Map of the Damage has a dual time line, a departure from your other books. Why did you take this new approach?

Sophia: When I originally thought about writing the book, it only had the 1940s strand. That’s where everything began: with Livy, walking away from a bombed-out house. But at the time, my first book (The Silversmith’s Wife) had just come out, and I was seen as a writer who concentrated on the 18th and 19th centuries, so I just put the idea away and wrote a novel based at the Victorian seaside (The Widow’s Confession). But the hook stayed with me, and simmered away in the back of my mind. And the idea of having this central place, the Mirrormakers’ Club, with its central mystery, and two timelines which mirror each other, made the book come to life in my mind. In essence it’s a dialogue between two women who are both wrestling with their times.

Also a plot device, I’ve always been intrigued by dual timelines. I remember reading Anya Seton’s Green Darkness when I was very young (it moves between the 16th century and the 1960s) and I was absolutely fascinated by it. But it’s very hard to do, I discovered!

Kate: What were the inspirations behind the book and why did you choose the periods you did?

Sophia: The voices of Livy and Charlotte were very clear to me from the beginning, so I was lucky with that, so although they weren’t based on real people, they came to life very quickly. In terms of themes, the book really is a depiction of passion – and there are so many books which do that beautifully and which I’ve been inspired by, such as The End of The Affair by Graham Greene.

Place is really important in the book, and the Mirrormakers’ Club is inspired by some archival research I did at London’s Goldsmiths’ Hall, on the architect Philip Hardwick and his building of the Hall. For Charlotte’s home, I visited Waddesdon Manor – Redlands doesn’t look like that, but the atmosphere – sequences of perfumed rooms, and the Bachelors’ Wing – is inspired by it.

My wish is always to create a kind of complete world, which the reader feels they can walk into, and I love the juxtaposition between the two worlds here. There is the 1940s: rationing, bombing, shock, contrasting with Charlotte’s 1840s life, which is full of luxury and decadence – she has too much of everything, which is its own problem too: she has to create her own sense of urgency.

Kate: Who was your favourite character and why?

Sophia: It’s so difficult because I feel affection for all of my characters. At a push my favourite is Henry Dale-Collingwood, the architect of the Mirrormakers’ Club. I love him because of his sarcasm, and because he’s a bluff workaholic who finds himself absolutely blindsided by his feelings for Charlotte. There’s something about that helplessness in the face of emotion which is very endearing. Also, I had to make Charlotte fall in love with him, so I suppose it’s good I like him too!

Kate: Do you think historical fiction has any relevance for today, i.e. is there any correspondence for example between the hardships endured during the Blitz and our current 'lockdown' situation?

Sophia: I think history always has parallels. What I always try to remember when writing is that the people living in that time didn’t know what the ending was. During the Blitz, lots of people had their bags packed in case of invasion. The victory narrative that we’re all so familiar with was way in the future for them. So that sense of adversity, and uncertainty, chimes with what we’re feeling now – and the fact that many people endured it and carried on their lives is a comfort. I do think that uncertainty is something we’re not really used to now, and we have the illusion of control. Whereas in the past, that was built into life, in a way: the expectation, perhaps, of illness or ill fortune, and the countering of that in the culture, whether through religion, or through rituals such as mourning. We think of the Victorians always wearing black, and sometimes they’re mocked for that, but in fact that mourning was a signifier of loss. It gave someone space to grieve and was an outward sign of the process they were going through. I’m not sure we give each other that space, these days. We don’t allow for uncertainty and loss, and it shocks us hugely when disaster comes.

One more thing: it’s a huge comfort to compare medicine today with the medicine of 150 years ago – once you’ve studied history you can only be crawling-on-your-knees-with-gratitude at the advances which have been made.

Kate: What was the most difficult part of writing the book?

Sophia: I found it hard to balance the writing with my day job. I have written all of my books whilst working full time, but this book felt particularly grueling, perhaps because I wrote a lot of it during the winter, and the last thing you want to do at 8pm on a winter’s evening is turn on the computer! There is always a difficult point for me, in each book, when the first draft is done (I love writing the first draft) and you have to start wrestling, really wrestling with the material and editing it in quite a brutal way. There was a long editing process with this book, and although I felt every moment of it, it was worth it. It always is.